By Rachel Davies, BioLinks West Midlands Project Officer

Its common name is derived from old English, with ‘ēare’ meaning ear and ‘wicga’ meaning insect. This is a term that may have arisen from the resemblance of their wings to the shape of a human ear, although it may also come from the legends of earwigs crawling into people’s ears – I am glad to say they don’t do this, it is just a myth!

However, this myth still carries through to today, and as a child, I remember being wary of them for that exact reason. I also remember finding them in unexpected places, such as on clothes brought in from the washing line and inside the umbrella on our picnic table! Thankfully, with age, I’ve learned that they will not invade my ears and that they are an essential part of many ecosystems outside our homes – they just happen to be flat tough-bodied insects that can sneak into the smallest spaces!

As I’ve come to love and appreciate these insects, I’ve learnt so much about their biology and ecology, with some surprising findings! Firstly, we have more than one species in the UK. Secondly, they show parental care (very uncommon for insects); thirdly, their delicate wings have been inspiring designers and engineers.

Read on as I share the things I’ve learned over the years, and help these misunderstood insects get some well-deserved limelight.

Earwig Morphology

Earwigs belong to the class Insecta, which is the largest group within the phylum Arthropoda, and to the order Dermaptera. Insects are characterised by having a three-part body, a hard exoskeleton, three pairs of jointed legs, compound eyes and one pair of antennae.

Some earwigs can have no wings (known as apterous), but in the UK, all species have two pairs of wings. The forewings are leathery, forming short wing cases, and the hind wings are large, membranous and semi-circular. Their hind wings are folded fan-like and held under the wing cases, and they are one of the most compact wing folding examples seen in insects – they open up to roughly ten times the size! Because they are stored so compactly, it does not compromise their ground mobility or increase their size unnecessarily. Taking inspiration from nature, researchers have looked at the complex folding of earwig wings and how their structure and function may be applied to design and engineering projects.

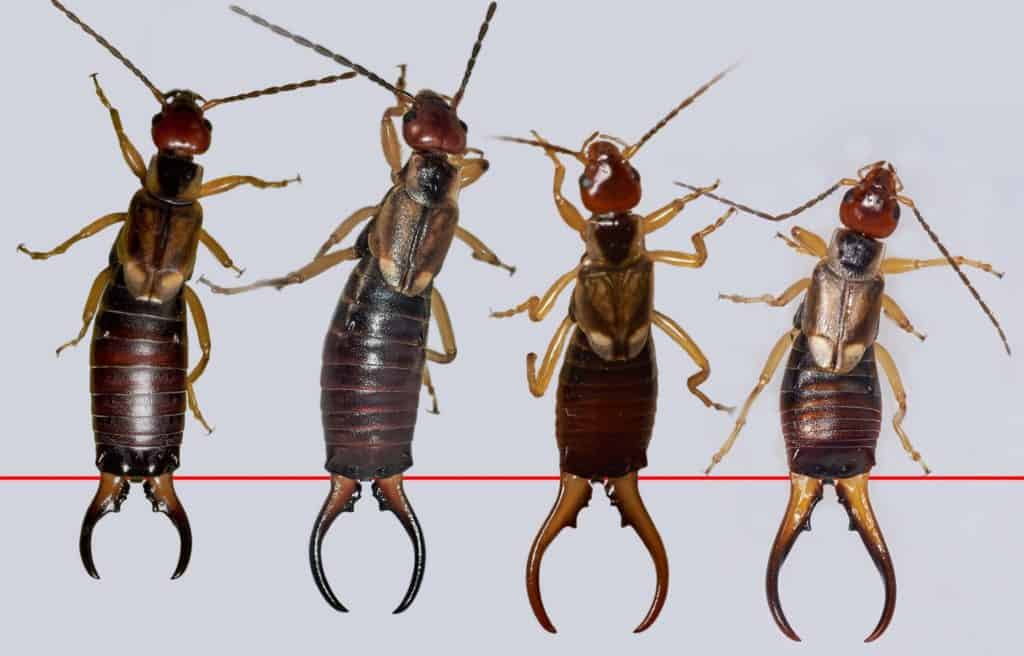

Earwigs also have characteristic cerci (a pair of appendages at the end of the abdomen), which are modified into a set of pincers. Pincers are usually bigger in males and are more curved when compared to the relatively straight pincers in females. Pincers are used for a variety of tasks, such as defence, grabbing prey, and mating.

Earwig Reproduction

Earwigs typically mate in the autumn, with the adults approaching each other backwards and mating end-to-end. Male spermatophores can be retained in the female for a few months before fertilisation takes place. Eggs will hatch in spring, and the nymphs (known as wiglets) will go through four or five instars between spring and mid-summer before reaching maturity. Wiglets look like smaller versions of adults at all stages as earwigs undergo gradual metamorphosis and have no pupal stage.

Earwigs are unusual in the insect world as they show parental care. Female earwigs create a nest to lay their eggs in, which they then guard. Females will also keep the eggs clean until they hatch by removing fungal spores – they do this by periodically licking the eggs. Once the eggs hatch, the female will guard the young until they are ready to fend for themselves. Plus, there are some species that are known to help even more by feeding the young.

Identification

There are nearly 2000 species of earwig in the world, but only 4 species occur in the UK. The four species of earwig present in the UK are: Common, Lesser, Lesne’s and Short-winged. The Common Earwig has the greatest distribution and can be found throughout the UK. The Lesser Earwig has a lesser distribution, but can be found in approximately half of the UK. Lesne’s Earwig is more restricted, being mainly a southern species, and the Short-winged Earwig is highly restricted, being found on the South-East coast only.

Earwig identification involves looking at the length and colour of the body, the visibility of folded hind wings and the shape of the pincers (particularly the pincer base and the presence or absence of teeth).

Common Earwig

Scientific name: Forficula auricularia

Length: 12-20m

Colour: dark chestnut brown

Wings: ends of folded hind wings are visible in both sexes

Pincers: male pincers are curved, widened at the base and toothed at the base. The widened base makes up less than half of the total pincer length. In females, the pincers are almost straight.

Lesser Earwig

Scientific name: Labia minor

Length: 5-7mm

Colour: dull yellow-brown

Wings: ends of hind wings are visible in both sexes

Pincers: pincers slender in both sexes but with a slight curve in males. No teeth present on pincers.

Lesne’s Earwig

Scientific name: Forficula lesnei

Length: 8-10mm

Colour: light brown

Wings: no hind wings are visible in either sex

Pincers: male pincers are curved, widened at the base and toothed at the base. The widened base makes up about half of the total pincer length. In females the pincers are almost straight.

Short-winged Earwig

Scientific name: Apterygida media

Length: 8-20mm

Colour: brown

Wings: no hind wings are visible in either sex

Pincers: male pincers very long and curved with 1 or 2 teeth present. In females the pincers are almost straight.

Instars of all species will have slender pincers; on later instars, a ‘w’ shaped wing bud should be visible.

Finding Earwigs

Earwigs are nocturnal, so searching for them by torchlight can give good results. When searching for them during the day, you can find them by checking underneath bark and logs, underneath stones and in leaf litter and other dead vegetation, where they will be sheltering. If you are looking for earwig nests in spring, looking under stones will yield the best results; however, they are very difficult to find.

Recording Earwigs

Earwig records are managed by the ‘Grasshoppers and Related Insects Recording Scheme’. Any records submitted to the scheme will be checked and verified by an expert before being made available on the NBN Gateway. You can find the recording scheme on Twitter @GrasshopperSpot.

Records can be submitted through the iRecord Grasshoppers mobile app or through the iRecord website, using the ‘Grasshoppers and allies’ species group form.

So next time you see an earwig, take a closer look, and hopefully, you can use the information here to help determine the species!

This blog has been created as part of the FSC BioLinks project, which focuses on invertebrate identification. If you would like to get involved with the project, you can view all our heavily subsidised courses and volunteer days here.