A biodiversity blog by Rachel Davies

Leeches are often disliked as they are known for sucking blood, so disliking them is understandable if this is all you have been taught about them. In reality, only one species of leech is known to feed on human blood in the UK, the medicinal leech, Hirudo medicinalis. However, its normal diet consists of blood from other mammals, amphibians and fish. Also, due to its medical uses, it has been harvested in great numbers in the past and is now present in only localised areas of the UK. Our other species of native leeches all feed on a range of wildlife, but none feed on humans. So, the chances of having a leech attach and feed off you are pretty slim!

As leeches are often misunderstood, they receive little attention, and as a result, they are an under-recorded group in the UK – even though leech identification can be done out in the field! BioLinks is taking this opportunity to help you learn a little more about these animals and hopefully break the misconception that they are scary creatures…

Freshwater Leech Biology and Ecology

Leeches belong to the phylum Annelida- the same phylum that earthworms belong to. This means their bodies have true segmentation. However, unlike earthworms, leeches have a fixed number of body segments from hatching, 34 segments (Elliott and Dobson, 2015). Leeches also have an anterior and posterior sucker which earthworms lack. These suckers are disc-shaped and are used for locomotion and feeding. The posterior sucker is mainly used for locomotion and the anterior sucker is mainly used for feeding and holding onto a host whilst doing so. These morphological modifications, along with a flexible, muscular body and a well-developed sensory system, allow leeches greater agility and the ability to actively pursue prey – which is highly beneficial given that all leeches are predatory or parasitic carnivores (Elliott and Dobson, 2015). Leeches will often be seen suckered onto objects in water. They will swim, but typically they use their suckers to get around, giving them a characteristic looping movement.

UK Leech Taxonomy

In the UK we have 17 species of freshwater leeches (Elliott and Dobson, 2015). UK leeches split into two separate orders- Rhynchobdellida and Arhynchobdellida. Working out the order your specimen belongs to is the first step in leech identification. The main difference is the presence or absence of an eversible proboscis, this is a tube-like organ which is pushed into the skin of a host to enable blood feeding (Elliott and Dobson, 2015). The eversible proboscis is present in Rhynchobdellida and absent in Arhynchobdellida.

In the order Rhynchobdellia, there are two families:

- Piscicolidae

- Glossiphoniidae.

And in the order Arhynchobdellida, there are three families:

- Haemopidae

- Hirudinidae

- Erpobdellidae

The infographic below shows the different feeding preferences of each family.

The Lifecycle of a Leech

Leeches are hermaphrodites, meaning each individual has both male and female reproductive organs. However, they can also reproduce sexually – with some species having a breeding season. The time between mating and egg-laying varies between species.

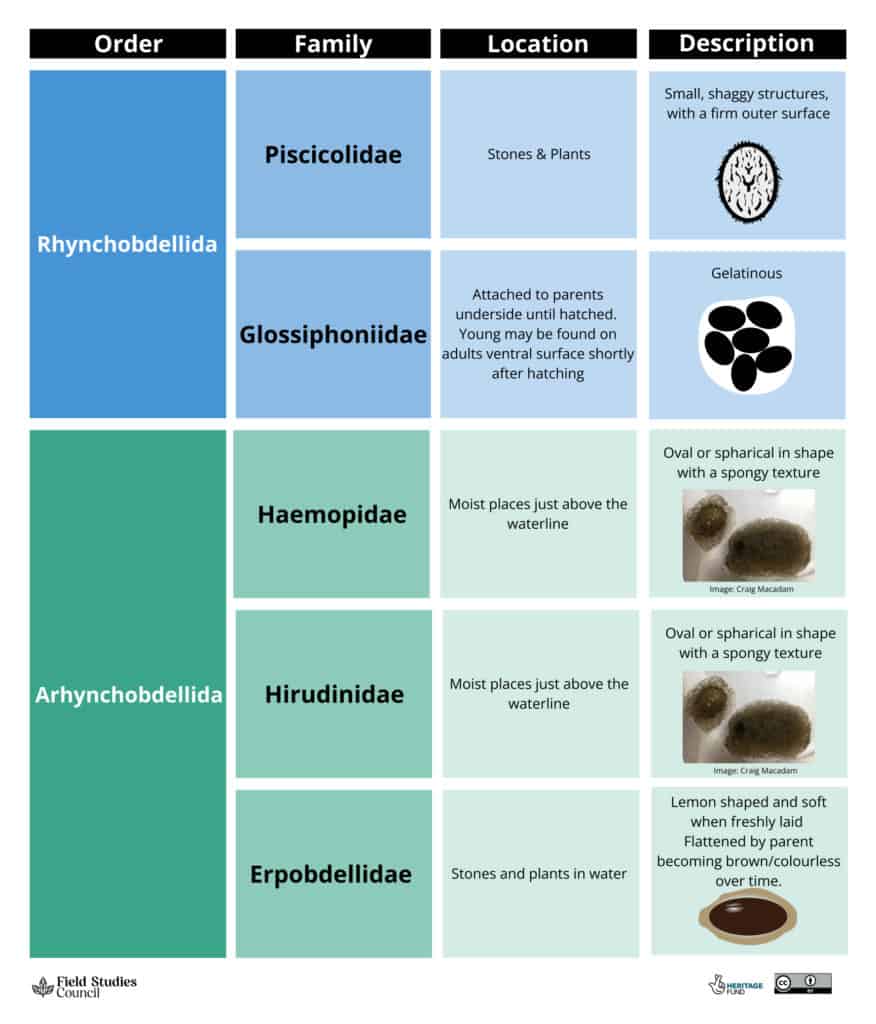

Young leeches develop in eggs, which are enclosed inside cocoons. The number of eggs inside an individual cocoon varies between species (Elliott and Dobson, 2015). Cocoons are mainly laid on objects either in the water or just above the water line. However, one family of leeches, the Glossiphoniidae, brood their fertilised eggs and carry their young – which is a lot more parental care than most invertebrates get!

The developmental time of eggs inside cocoons varies depending on both species and environmental conditions, but when the eggs hatch the young leeches resemble adults – just smaller! This is because leeches are epimorphic, meaning they have the same form in successive stages of growth.

Leech cocoons are fascinating structures, and they can be used to identify the parent leech at least to family level. The infographic below describes the appearance of cocoons for each of the five families found in the UK.

Finding Leeches

When surveying for leeches, the best collection method is hand-searching. They can often be found clinging to the underside of stones, or near the bases of reeds and rushes. They can also be found on the underside of submerged leaf litter. The best way to collect a leech is simply to wipe it off the object it is on using a finger and then wash it off your hand into a collecting pot or a tray (Elliott and Dobson, 2015).

If you’re familiar with pond dipping, you may have found leeches when using pond nets and plastic trays or buckets to empty your catch into. They can be found regularly when using this method, although usually in smaller quantities. You are most likely to spot one clinging onto the tray once everything else has been released back into the pond.

To handle leeches, it can be useful to place them on a white plastic spoon – this allows you to get a closer look, and the thin plastic allows enough light to penetrate through so you can see useful features, such as eyes.

Leech Identification

Leech identification can occur when the specimen is live, with many species able to be identified in the field with just a hand lens. However, a microscope can be useful for some species, and live leeches can be temporarily immobilised in soda water for 10-15 minutes to make microscope work easier (Elliott and Dobson, 2015). They can be released afterwards to their original location.

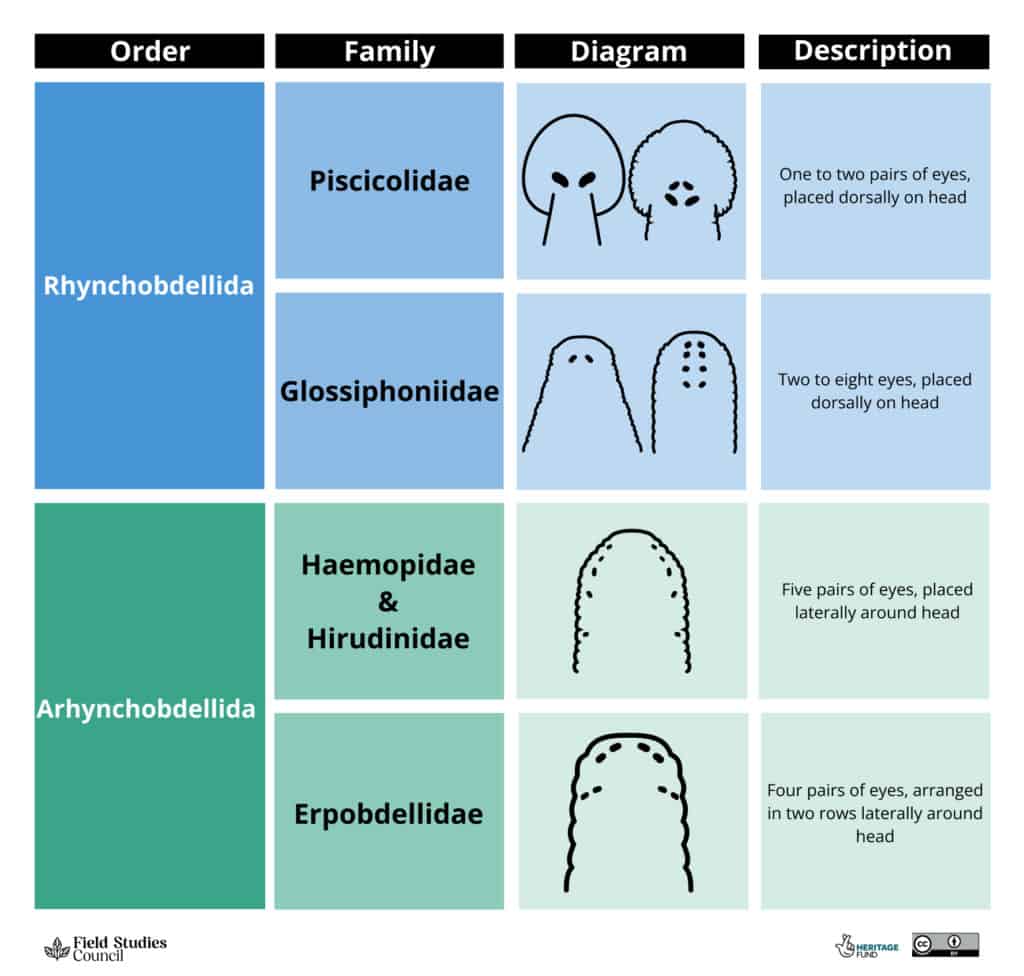

When identifying a leech, it involves looking at several features, some of which can be tricky to spot. However, to identify a specimen to family level, it is a case of looking at the number of eyes they have and the arrangement of them (Croft, 1986). In the infographic below, we show the five different families of leeches found in the UK and the specific eye arrangement each family has. After reaching family level, a key will be needed to take a specimen to species level.

Records can be submitted to iRecord and it is recommended to include photographs where possible.

Useful Links and Resources

- The book ‘Freshwater Leeches of Britain and Ireland’ is a fantastic resource for leech identification and can be purchased from the Freshwater Biological Association here.

- The Freshwater Habitats Trust has been working to conserve the Medicinal Leech, and more information on the Medicinal Leech Recovery Project can be found here.

- Join us on a freshwater ecology course to learn more about leeches and the other species present in the underwater world.

- Complete our online course ‘Discovering iRecord‘ to learn more about this tool and biological recording.

References

- Croft, P.S. (1986). A Key to the Major Groups of British Freshwater Invertebrates.

- Elliott, J.M. and Dobson, M. (2015). Freshwater Leeches of Britain and Ireland.