Dan Puplett has just written and illustrated the new WildID fold-out guide to Mammal tracks and signs. Here Dan answers our questions about the guide and tells us more about how you can get started with mammal tracking, even if you have never tried it before.

What’s the new guide all about?

Many mammals are elusive, and often most active at night. But their tracks and signs can tell us a lot about which species are present in an area.

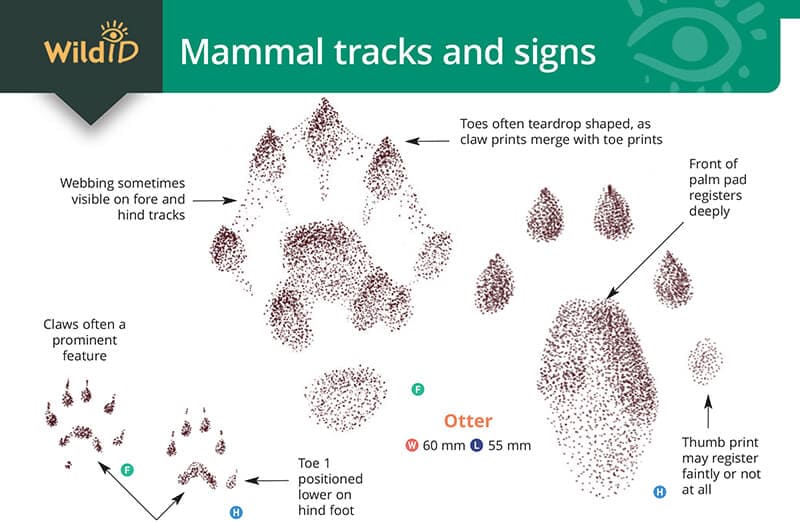

The new WildID guide shows the tracks and signs left by many of Britain’s wild and domesticated mammals. It includes footprints as well as feeding signs, scat, homes and more. My aim was to write a helpful introduction guide for beginners which was also useful for students and ecologists.

Although tracks are common, you don’t always find perfect prints. So the concise labels highlight the key identification features to look out for. As well as the basics, it includes some more difficult to identify tracks based on recent discoveries by wildlife trackers. Small mammal tracks (left by mice, voles, shrews and others) are tiny, but with care these can be identified to species.

Tracking is a fascinating skill. It helps people of all ages and levels of experience develop a deep familiarity with the natural world as well as contributing to wildlife conservation.

If you have never looked for tracks before, how do you start?

The key thing is to just get out there and start looking!

For tracks find places with good substrate such as areas of mud or sand. To start with, you will probably find the tracks of dogs most often. Even though these aren’t as exciting as finding the tracks of wild animals, it is still worthwhile looking closely to get familiar with what differentiates dogs from other mammals such as foxes. Then when you see something that is not a dog it will be more obvious.

Engaging your senses and sense of curiosity is an important part of it as well. Making notes about what you observe, sketching and taking photographs can really help the learning process. Pay attention to all sorts of clues and signs such as marks on trees and holes in the ground. Even if you’re not sure what you’re seeing at first, the process of noticing things trains your brain to pay more attention. With practice you’ll become more accurate at identifying signs and tracks to species level.

The Mammal Species Hub is very useful for finding out more about the ecology and behaviour of particular mammals. This really helps when studying tracking and for learning where you are likely to find particular signs.

There are also various track and sign courses where you can learn from trackers in the field. I run courses myself, see Nature Awareness, sometimes through Field Studies Council. The Mammal Society also runs excellent courses.

Can you submit biological records of mammal signs?

Yes! Many different mammal tracks and signs can be submitted as biological records. Footprints include of badgers, hedgehogs, otters, foxes and mink. Signs include badger setts and latrines, squirrel dreys and feeding signs, otter spraints, rabbit warrens and many more.

When it comes to surveying for mammals we often encounter tracks and signs more than we see the animals themselves. So this is a really practical way in which the ancient skill of tracking can be applied to conservation. Conservation relies on good biological records and citizen science is an important part of this. We need a clear idea of mammal populations, trends and distribution for knowing when and where action is needed.

A great way to submit your records is by downloading the Mammal Society’s Mammal Mapper app. You can submit records for a wide range of species based on tracks and signs as well as direct sightings.

You have drawn all the mammal track images yourself. How do you go about this?

The first stage is spending a lot of time in the field getting to know as many tracks on signs as I can and studying the different identification features.

I have collected a lot of photographs of mammal tracks over the years. I use several different photographs as source material for my drawings to help pick out the key diagnostic features. In cases where I don’t have clear photographs of a particular mammal’s track I also draw upon photographs taken by friends in the tracking world. At times I trace the rough outline to make sure the proportions are accurate, and then I fill in the detail by eye, using lots of dots! This takes a lot of time but it is also an enjoyable process. For a number of the tracks I did several versions until I ended up with one that I was happy with!

It’s actually really tricky to illustrate a ‘typical’ track, as there can be so much variation depending on the substrate and the amount of weathering in the track. For the most part I have drawn tracks as they would be seen in very good substrate. This is to help illustrate the key features to look out for as well as to develop a good ‘search image’ which is an important part of tracking. With experience we can start to pick up these features even when the track is partial or very faint.

The style of track images that I produced for this guide is similar to those that I drew for the earlier WildID guide to British bird tracks and signs.

How did you first get involved in tracking?

I’ve been fascinated by the natural world since I was very young and I have studied field natural history for most of my life. Around 2002 I encountered various tracking teachers who really inspired me about the art of tracking. I became happily obsessed with it and have been studying tracking intensively ever since! I got involved in the tracking evaluations in 2012, and in 2021 I managed to gain my Level 4 (100%) certificate in Track & Sign (see below). The tracking journey is endless though and there is always more to learn.

My background is in conservation and environmental education, and I teach naturalist skills generally, and tracking in particular, to people of all ages. I provide training for professional ecologists and conservationists as well as interested members of the public, including children. I also apply tracking in various wildlife surveys and of course for my own enjoyment and connection to nature.

You are certified through Cybertracker Conservation. What’s that?

Cybertracker Conservation is a rigorous field-based assessment in tracking. It is now the international standard for evaluating trackers in the field. This system was started in South Africa in the 1990s by conservationist Louis Liebenberg alongside indigenous trackers. They recognised that this ancient indigenous skill was slipping away. They wanted to find out who were the remaining skilled trackers and to train a new generation. The certification system helps employers to hire the best trackers for eco-tourism and research.

Louis developed a GPS based software so these people could record what they found in the field. This is where the name Cybertracker came from. The name stuck although it is a little misleading because the evaluations don’t have anything ‘cyber’ about them! It is very much a practical test of observer reliability.

Later the system spread to America, the UK, the rest of Europe and other parts of the world. I really recommend the two day Track & Sign evaluations for anyone who has an interest in tracking. The assessment involves 56 questions over the course of two days, covering a wide range of tracks and signs including those of mammals, birds and insects and more. At the end of the evaluation you get a percentage score. It’s a great system because even if you get a question wrong you learn a lot in the process. There are also trailing evaluations which assess your ability to follow and observe animals without disturbing them. So, if you’re just starting out you’ll still gain a huge amount from an evaluation. It may sound daunting but you actually find yourself among a friendly, fun and supportive community of trackers.

Is there anything else you would like to add about the WildID guide, or tracking in general?

I would like to thank Field Studies Council Publications as well as a number of my tracking friends including David Wege and Bob Cowley who gave useful feedback on an earlier draft of the guide, and John Rhyder who has done a lot of valuable research into how to differentiate some of the smaller mammals. I’m also grateful to my tracking mentors, peers and students (as well as all the wild animals of course!) who over the years have taught and inspired me in many ways and continue to do so.

As for tracking in general I just really encourage anyone with an interest in nature to go out and give it a try. Our human species has been tracking for tens of thousands of years and while these skills may lie dormant I think we all have the potential to be trackers. Most of us have a fascination with the natural world and there is also great appeal in detective work and solving problems.

Tracking is a fantastic way to connect to nature and has been described as ‘becoming fluent in the language of the land.’ It helps us to become better all round naturalists and deepens our understanding of ecology as well as helping us conserve and appreciate mammals and other wildlife.

Dan Puplett is a naturalist, tracker, conservationist and environmental educator. You can find out more about his work at his website.