Blog by Pippa Dashfield

A study by the university of Essex revealed that just five minutes of “green exercise” can produce rapid improvements in mental wellbeing and self-esteem, with the greatest benefits experienced by the young and middle aged. Living on the Isle of Cumbrae, I see lots of beautiful wildlife day in day out, however, like the vast majority, I don’t make the conscious effort to identify or name it. I decided to get outside, get my “green exercise”, and have a look around my local area to see what I can identify with the handy FSC guides. The guides I used are:

- Guide to summer coastal birds

- Guide to winter coastal birds

- Guide to common seashells of Britain and Ireland

- Guide to common seaweed

- Guide to the UK cetaceans and seals

- The rocky shore name trail

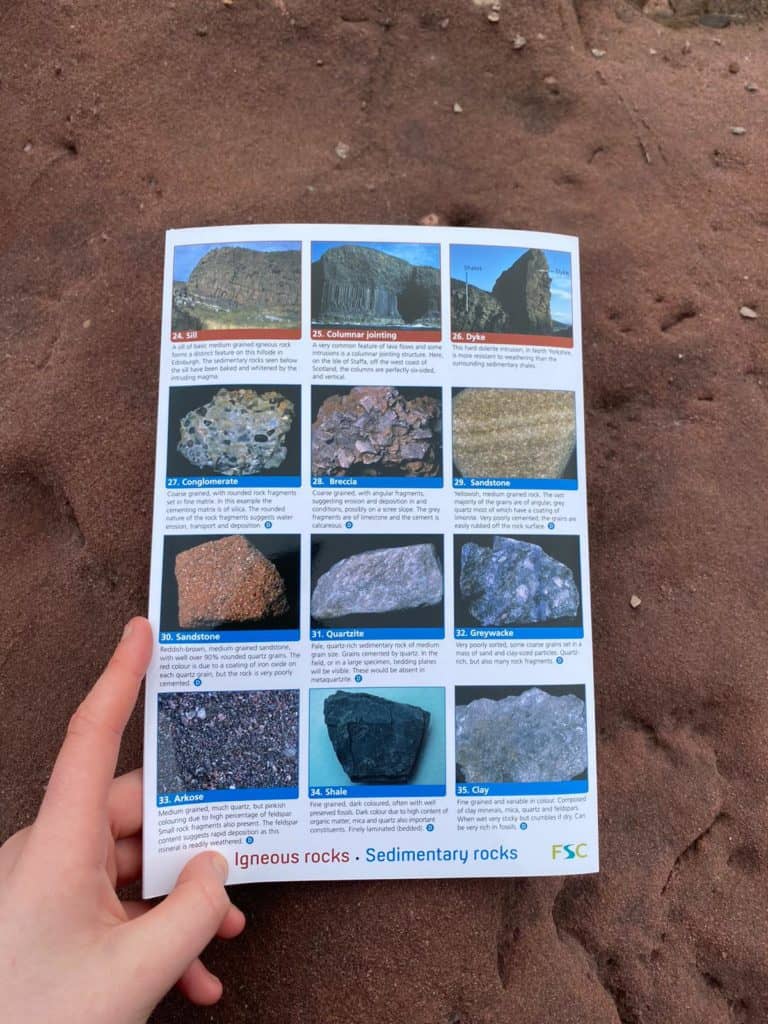

- Guide to rocks

FSC is one of the UK’s leading publishers of wildlife identification guides, with 230 guides available. There are guides for beginners all the way through to your more niche titles, for those who have that special interest. All of the guides are simple, easy to use and come laminated, which is ideal for use in the outdoors.

I started my walk from FSC Millport centre right by Lion’s Rock, the green point on the map. After talking to my peers, I knew that Lion’s Rock is a dyke that intruded through the surrounding rocks 23-66 million years ago – however, the rock type was still unknown to me. Using FSC’s Guide to rocks and a hand lens, I identified Lion’s Rock to be Gabbro, a dark coloured, course grained igneous rock. The crystals in the Gabbro are mostly the same size and have dark areas of pyroxene rich minerals and some lighter areas of plagioclase feldspar and quartz.

Next, I found myself at Farland Point. Farland Point has a multitude of exciting wildlife, however as I still had the guide to rocks still handy, I decided to start there. I was able to identify quite quickly that it was red sandstone, from the obvious red colour. The sandstone was reddish-brown, medium grained and has over 90% rounded quartz grains. The red colour is from a coating of iron oxide on each quartz grain. The reverse side of the guide taught me a lot more about the rock. It is fine grained and well rounded, meaning it has been transported a long way by running water, ice, the sea, or the wind. Quartz is the most common mineral in this sandstone, making it durable and resistant to erosion and weathering.

Then, I wanted to try and identify some birds that I see almost daily, and finally put a name to them. The guides I used were FSC’s Guide to winter coastal bids and FSC’s guide to summer coastal birds. Through my binoculars I noticed 2 oystercatchers sitting on the red sandstone by the shore. Oyster catchers (Haematopus ostralegus) are residents around the uk all year, usually seen around the coast and estuaries, heading inland to breed and lay their eggs in the summer. They have a strong distinctive orange beak that it uses to prise open molluscs such as cockles and muscles and to probe for earthworms.

The second bird flew right past me but then came back and sat 10m away, allowing me to get a good look at what it was. I’m pretty sure it was a little rock pipit (Anthus petrosus). Rock pipits can be seen on rocky coasts around the UK and Ireland all year round, easily identified by their dark plumage, smudgy markings, narrow white eye ring, and long dark bill. Their nests are usually well hidden in a rocky crevice or in dense vegetation and they are able to raise two broods of chicks a year.

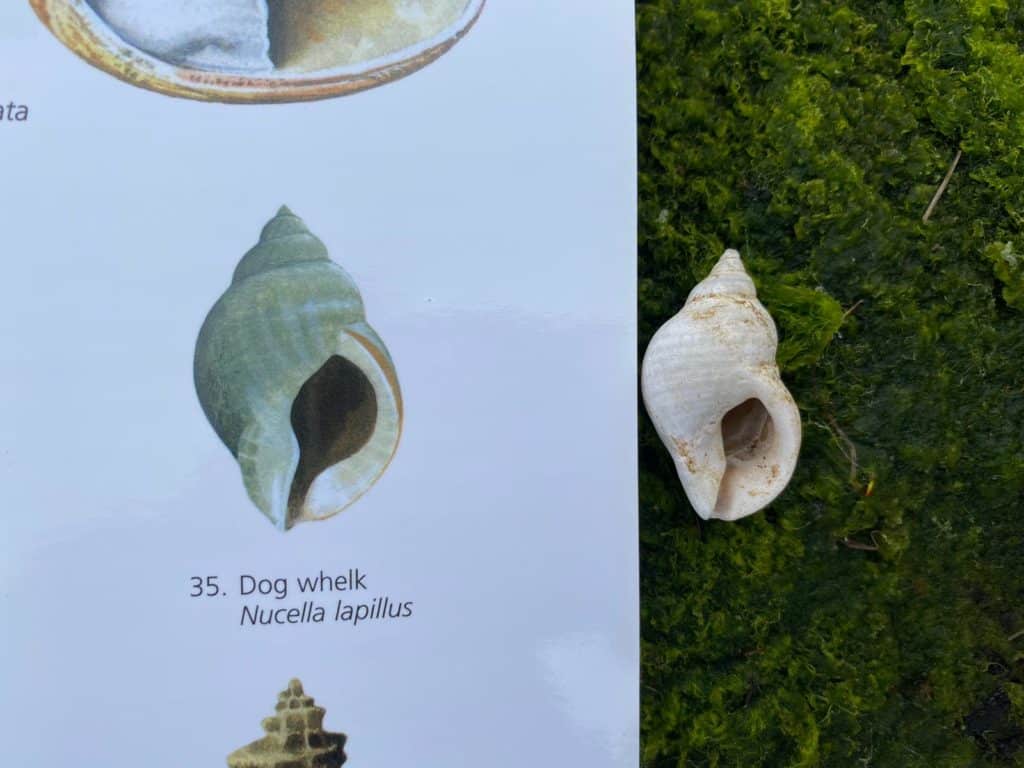

Still at Farland point, I headed down towards the rocky shore to see what I could discover with the guide to Common seashells of Britain and Ireland and the Rocky shore name trail. I started at the upper section of the shore, where all the pebbles and shells were and in 15 minutes, I identified quite a lot!

The first shell identified was a Dog whelk (Nucella lapillus). They are around 6cm high, have roughly 6 whorls and 12 spiral-shaped ridges on the largest whorl. The outside is sometimes patterned and a white, cream, or orange colour.

The next shell I saw was the common Limpet (Patella vulgata). Limpets are very common on a rocky shore; they are usually 2.5cm high, 6cm across and cone shaped. The outside is usually grey, brown, or yellow and the inside a glossy white colour. They also feed on young seaweeds.

The last shell I could spot in the upper section of the shore was the edible periwinkle (Littorina littorea). Common throughout the shore sections, edible periwinkles are around 5cm high and easily identifiable by their pointed spire, steep sides, and ridged whorls. The outside is a grey, brown, or black colour.

Moving down to the middle and lower sections of the shore I discovered some exciting living animals. I found a Beadlet anemone attached to the sandstone. They have a soft body, which is attached to the rock by an adhesive disc. They catch prey using tentacles armed with stinging cells, and some species – the Beadlet anemone being one – can retract their tentacles.

While looking at the anemone I spotted some barnacles (Cirripedia). Barnacles are in the phylum Arthropoda; class Crustacea which is a very common group, including lobsters, crabs, sea slaters and shrimps. Barnacle larva is free living, but when it turns into an adult it lives inside a case of shell plates, cemented firmly to the rock. At high tide, their legs extend out of the case and they filter feed on particles in the sea water.

On my way back from the shoreline, (trying my best not to fall over) I spotted a dead sea urchin (Echinoidea). Sea urchins are radially symmetrical and have an internal system of water filled channels extending into many tubed feet along their body surfaces. These relax and contract allowing them to move. Sea urchins have a hard rounded shell covered in spines. They graze on plant and animal material on rock surfaces.

As I was leaving Farland point I wanted to try and identify some seaweed as it’s never been something, I’ve given much thought about, apart from the fact it can get quite smelly. With the Guide to common seaweeds, I identified some gut-weed (Enteromorpha linza). Gut weed is a common seaweed often found in rock pools all around the UK. It roughly grows up to 20cm and has bubbles of air trapped in fronds, which is why it floats.

While walking to Kames Bay to try and find different shells to identify, I kept my eyes open for more birds. I was able to identify 2 more using both of the bird guides. One of the two was a redshank Tringa tetanus). They’re found all over the UK and breed in salt marshes, water meadows and lake banks. Often feeding at the water’s edge by probing for invertebrates in the soft mud, they are identifiable by their distinctive ringing call.

The other bird was a Curlew (Numenius arquata). Curlews are the UK’s largest wader, found around coastlines, moors, heaths, pastures, and estuaries. The breed in April-July and subsequently nest on the ground among vegetation, often on moors and wet grasslands. Identifiable by their slow steady flight, wingbeats are even and continuous and can be seen feeding on mud flats at low tide.

It was high tide at kames bay which isn’t the best time to look for shells and seaweed, however I still found two exciting shells. The first shell is a pod razor shell (Ensis siliqua). Razor shells are interesting as they burrow into the sand/mud and have two valves that are long and narrow but don’t close at either end. Their valves are long and straight, reaching up to 20cm and are usually a green or yellow-green colour. The one that I found had been slightly weathered so it was more orange/green.

The next, and last, shell I found on my journey was the banded carpet shell (Tapes rhomboides). They are usually around 6cm with a cream shell that has brown rays. Again, like the pod razor shell, the banded carpet shell was orange due to weathering. The fine concentric growth lines give it a striped appearance.

I didn’t expect to find and identify as much as I did on my walk, however, I now feel so much more confident in identifying and naming wildlife. Learning more about your local wildlife is a great place to get started and what better way than with some easy-to-use FSC guides. There are even some bundle packs that are ideal for getting started on identifying wildlife just in time for spring! Check out the guides and bundles here.